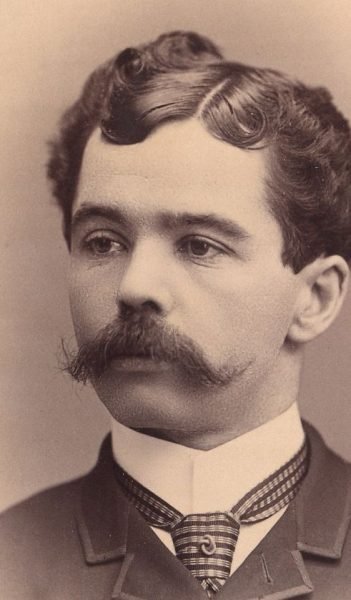

Richard Hague

The moderniser who followed in William Thompson's footsteps

History

Richard Hague began his career as a dancer. In his youth, he danced at the Alhambra and the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, before retiring due to a hip injury.

Following his retirement, Hague transitioned to teaching, eventually joining the National Training School for Dancing at Drury Lane. He was approached by Thompson in 1887 to join the faculty of the ballet school that Thompson was planning to open at Covent Garden. Hague initially refused the offer, but upon further convincing he decided to accept, becoming one of the founding teachers at the opening of the Covent Garden School for Ballet in 1888.

In 1890, Thompson created Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland for Marta Draeger. Thompson wished to include students in the ballet, planning for them to portray the oysters in the scene of the walrus and carpenter. This caused a debate among the school’s faculty as to whether such an endeavour was appropriate or even possible. Some argued that the students would not be able to handle the stage nor would they have been adequately prepared for the technical and maturity demands of performing alongside the troupe for the critics and audience. Others argued that the students had shown, in their daily instruction, that they could retain and execute choreography, and so there was little reason to suggest they could not be drilled to perform on the Covent Garden stage. Hague fell into the latter camp, arguing for the inclusion of students in the ballet. Eventually the inclusion camp won out, and Thompson choreographed the Polka des Huîtres in the first scene of the third act. At the ballet’s première, the Polka (save a few mishaps) went well and continued to do so for the duration of the run.

In addition to his teaching duties, Hague also performed the duties of balletmaster to the troupe, rehearsing the corps de ballet in dances created or set by Thompson. Hague continued to work closely with Thompson and by 1894 Hague was Thompson’s de facto second in command.

Opinions differ as to the extent of the assistance rendered by Hague to Thompson, the extent of Hague’s choreographic contributions under Thompson and the exact timelines of Hague becoming second in command at Covent Garden. It seems plausible that by the 1892 season Hague was contributing to “Thompson’s ballets” in a meaningful way, which then, as now, would have been entirely attributed to Thompson. Given the lack of records as to the exact nature of Hague’s contributions, some scholars argue that his involvement ended with simply rehearsing what Thompson had set while others argue that his involvement extended to choreographing entire key dances. However, as stated, the lack of sources makes this question, unfortunately, indeterminable.

In 1895 Thompson publicly expressed that he wished to retire at the end of the 1896 season. Hague had been privately forewarned of this announcement by Thompson, who had also shared his future vision for the troupe with Hague and expressed that he intended to nominate Hague for the position of balletmaster (later referred to as balletmaster in chief). Thompson did so, nominating Hague as the sole option for his successor.

Both announcements caused ripples through the backstage world of Covent Garden. Several of the older balletmasters who had been with Thompson since the days when the troupe was stationed at Her Majesty’s Theatre protested the succession on the grounds of seniority. Thompson was decided, and argued to the management that it should be Hague. Several interviews then proceeded, as Hague was asked to justify his position and future vision for the troupe. Despite the opposing voices, Thompson’s approval carried a great deal of weight and Hague was chosen to be the balletmaster following Thompson’s retirement.

For the 1897 season, Hague’s first task as balletmaster was to secure another première danseuse. The years 1895 and 1896 could be considered the years of Sarah Nicholson‘s reign as following Draeger’s departure in 1894, Nicholson was the sole première danseuse of Covent Garden. Thompson had not quite gotten round to promoting another danseuse to the rank before his retirement, though he had tried out a few sujets in leading rôles.

These trials served the dual purpose of testing other danseuses and reducing the burden on Nicholson, as one danseuse, however tireless, could not carry a whole season alone. Therefore, it was necessary for Nicholson to have “covers” to take on her roles when rest or circumstance required it. In 1895, two ballets were revived for Nicholson, Coppelia and The Sylph. The cover of Coppelia went to Lucia Rinaldi, whose vivacious and spirited portrayal of Swanilda was a success in its own right.

With Coppelia settled, The Sylph was contested between two sujets: Harriet Linwood and Marie Saunier. Thompson, unexpectedly to all, decided to give it to Saunier, which raised some eyebrows. Linwood and Rinaldi were generally considered to be the two strongest sujets at the time, with critics divided as to who they preferred. Thus, it had been expected that since Rinaldi had been given Coppelia to cover Linwood would be given The Sylph to cover.

Despite the initial critical skepticism, Saunier was quite well received in her performances of the rôle, With one critic conceding that:

“Perhaps our ballet master [Thompson] understands his art far better than those who seek to discredit him.”

The year of 1896 brought with it fewer backstage quarrels. Thompson was to retire at the end of the season, and his last ballet The Swords of Toledo, was created for Nicholson. As the ballet was new, it needed no cover as only Nicholson would dance it in its first season. The second ballet that was revived for her was The Buccaneers, which was covered by Linwood, with some critics quipping that it was perhaps an apology for being denied The Sylph.

Such was the position that Hague found himself in in 1897, where he had the task of choosing to elevate or import. Hague initially chose to import by engaging Maria Nardella, an Italian ballerina, to be première danseuse and reviving The Corsair for her. The Beauty of Ghent was revived for Nicholson in the same season.

Nardella demanded a new Pas de Deux to replace the Pas des Éventials of Act 1, Scene 2, and a new Variation for the Pas des Fleurs of Act 2. Hague obliged, turning to Auguste Péchard (the Official Composer of the Ballet Music to the Royal Opera House) for the music and choreographing the dances for Nardella. However, Nardella did not take well to London, disliking the English school of dancing as she believed its positions did not flatter her best. Additionally, Hague resisted Nardella’s attempts to have her costumes redesigned, something that annoyed the danseuse. As such, she stayed only for one year, departing London in early 1898.

Thus, in 1898, Hague finally chose to elevate Linwood (who he had cast as Gulnare in The Corsair and Agnès in The Beauty of Ghent) to the rank of première, returning Covent Garden to a similar “dual monarchy” it had seen in the early 1890s with Draeger and Nicholson.

Hague is best remembered as a moderniser and reformer. It was his directorship that saw Covent Garden move from the older “diva” led model to a more institutional model, which, though it still relied on star power, did not allow its danseuses unlimited privileges or demands.

Hague was disliked by Péchard, who compared him unfavourably to Thompson. The two men choreographed differently, which may have clashed with Péchard’s perceived artistic freedom. Thompson would ask Péchard for a waltz, polka or some other dance and Péchard would provide it, then Thompson would listen to the music and choreograph to its mood and accent. Hague, on the other hand, often thought of choreography first, devising entire variations that Péchard would then have to fit music to. Hague was also disliked by Nicholson for much the same reason, loss of perceived freedom. Her demands were now to be assessed and could potentially be refused, no matter how hard she pushed. Though Hague did accommodate many of her demands, he did push back on many others, and when he decided it was final he would not be convinced otherwise.

Hague also wished to diversify the music for ballet, and so sought to abolish the position of Official Composer of the Ballet Music. Péchard, having enjoyed a long and successful career that began with his appointment to the position in 1889, saw the writing on the wall and retired in 1903. For Péchard’s benefit, his final ballet score, Tristan and Yseult was premièred, with Hague providing the choreography. Hague then promptly abolished the position and began to commission new composers to compose, revise and supplement works, some of whom had never composed for ballet previously. His 1909 ballet Alcandra or The Amazons was his most successful creation, balancing his forward-thinking ideas with the conventions of classical ballet handed down to him.

Ballets

The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

- The Two Pigeons (1898*)

- Naïla (1900*)

- Fairest Isle (1902)

- Tristan and Yseult (1903)

- Yedda (1904*)

- The Two Peasant Girls (1905)

- Alcandra or The Amazons (1909)

- The Pearl of Iberia (1912*)

- The Fairy Doll (1912*)

- The Choice of Hercules (1914)

- The Red Masque (1914)

New ballet

New revival / new production*