Ballet in Opera

The re-introduction of ballet into opera London under William Thompson

History

Ballet as part of opera dates back to the beginnings of opera. It became formalised in the Baroque era under King Louis XIV; at his court in the Louvre and later Versailles, ballet became an integral part of the tragédie en musique as codified by Jean-Baptise Lully. This was later drafted into the conventions of Grand opéra, with Auber’s La Muette de Portici (1828) and Rossini’s Guillaume Tell (1829) both containing opportunities for ballet during the opera.

This convention was retained throughout the 19th century, and composers who wished to have their works played at the Paris Opéra were required to insert a ballet. Non-French composers often chafed at this, with Wagner famously objecting to the ballet being inserted into Tannhäuser in 1861. However, he was forced to concede but inserted the ballet into the wrong act, resulting in the opera being withdrawn after only three performances.

While ballet in opera was near-universal in Paris, the same could not be said for productions abroad. Even when grand operas such as Les Huguenots or La Prophète were exported, they were usually translated into Italian and had their ballets removed. This was also the custom in England, where the inclusion of ballet in opera was not usually the norm.

Re-introduction under William Thompson

William Thompson, drawing inspiration from Paris, as was his style, wished to restore ballet to what he believed was its proper place in opera. He constantly chided James Henry Mapleson (manager of Her Majesty’s Theatre) to allow him to do so, but Mapleson refused, believing that doing so would not please the public.

In 1883, Arthur Goring Thomas’ Esmeralda, an English-language opera, premiered at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The opera included a ballet in the second act which was successful and well received, but Mapleson remained unmoved by Thompson’s renewed pleas to transfer the innovation to Her Majesty’s Theatre.

This disagreement came to a head in 1884, when Covent Garden was staging a revival of Meyerbeer’s Gli Ugonotti and wished to invite Thompson and his troupe to stage the Act 2 and Act 3 ballets. This caused a quarrel between Thompson and Mapleson. Mapleson argued that the troupe were engaged by Her Majesty’s Theatre and therefore answered to him, and so could not freely perform at other theatres without his express permission. Thompson, on the other hand, argued that the troupe was simply resident at Her Majesty’s Theatre, not owned by it, and therefore answered to him. Closer examination of the contract revealed that the wording leaned in Thompson’s favour, and so, much to Mapleson’s chagrin, Thompson took a subsection of his troupe to Covent Garden to stage the ballets in Acts 2 and 3 of Gli Ugonotti.

The revival, including the ballet was successful, cementing Thompson’s opinion that ballet ought to return to opera. However, this success had the inverse effect on Mapleson, who, irritated by Thompson’s insubordination, flatly refused any future offers to stage ballets in operas at Her Majesty’s Theatre. This was one of the reasons that contributed to the break between Thompson and Mapleson, culminating in Thompson’s move to Covent Garden in 1887.

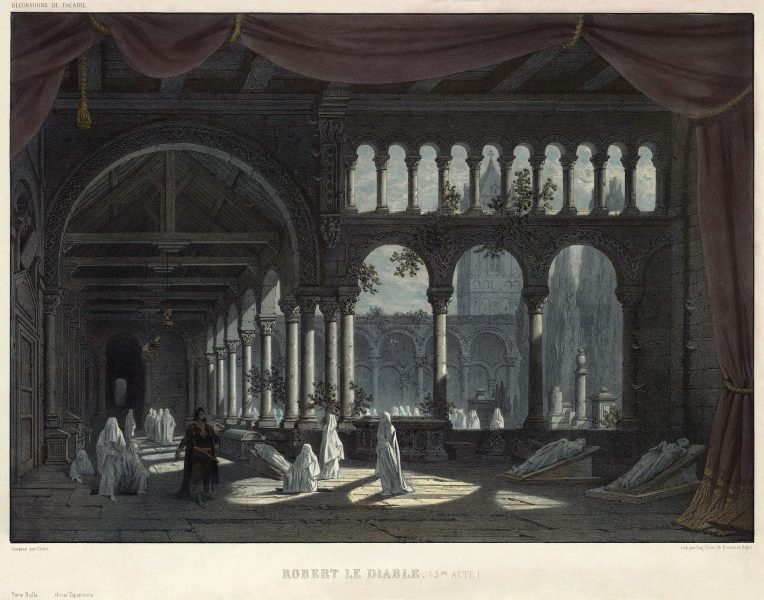

Once installed at Covent Garden, the management were much more receptive to Thompson’s attempts to stage ballet and opera. He began in earnest in the 1888 season, staging ballets in Verdi’s Aida, Bizet’s Carmen, Gounod’s Fausto, Rossini’s Guglielmo Tell and restaging the ballet in Meyerbeer’s Gli Ugonotti that he had staged at Covent Garden four years prior. He also inserted a ballet into Carmen, arranged from Bizet’s L’Arlésienne Suite No. 1. He would continue this with staging ballets in revivals of Meyerbeer’s Roberto il Diavolo (1889), Thomas’ Esmeralda (1890) and Meyerbeer’s Il Profeta (1890).

However, though he staged these ballets, they did not always remain in the repertoire. The extra ballet inserted into Carmen was eventually cut, as was the ballet of Il Profeta following its initial run. The ballet in Fausto was the most consistently retained, with the ballets in Gli Ugonotti and Aida being included or cut based on the needs of the day.

1889 Revival of Roberto il Diavolo at Covent Garden

Background

The 1889 revival of Roberto il Diavolo contained two main dance sequences: the Pas de Cinq of Act 2 and the Pas des Nonnes Damnées of Act 3. Thompson pushed for both dances to be included and eventually proved successful in his effort.

Thus, Thompson was now presented with the challenge of casting the rôle of Héléna, the abbess. Emma Ashfield was the natural choice, and Thompson had in fact first approached her, but she declined the rôle on account of her injury and demanding rôle of Marguerite in the revival of Faust. Marta Draeger would have been chosen next, but she was also dancing Médora in The Corsair and the Spirit of Pride in Faust and Thompson did not wish to overload her further.

Thompson then considered his sujets, Ivy Gregson and Sarah Nicholson. As Nicholson had quite impressed Thompson in her performances as Gulnare, he decided that she should portray the abbess, while Gregson would lead the Pas de Cinq. Alongside Gregson, Mary Butler and Lucia Rinaldi were cast in the Pas de Cinq, accompanied by Charles Jennings and Frederick Hale.

Once Draeger learned of this, she expressed to Thompson her wish to portray the coveted rôle of the abbess, created by the legendary Marie Taglioni. She assured Thompson it would not be too much for her, even stating that she could have Nicholson as an alternate to alleviate his concerns. Thompson eventually acquiesced, agreeing to divide the performances between Draeger and Nicholson.

Nicholson was predictably furious when she learned of this and accused Thompson of undue favouritism. This accusation was seconded by Butler, who (unknown to all) had privately asked Thompson if she could share the rôle of Héléna with Nicholson and was flatly denied. Despite these complaints, the revival of Roberto il Diavolo premièred as planned, with Draeger as Héléna. This incident could be cited as the beginning of Nicholson’s personal resentment towards Draeger, which up until that point had not passed the usual levels of professional competition.

Dances

Acte 2

1) Chœur Dansé

2) Pas de Cinq [3 dames, 2 hommes]

a) Andantino quasi Allegretto

b) Allegro Moderato

c) Moderato [MM Jennings, Hale]

d) Allegro leggiero [Variation I – Mlle Butler]

e) [Variation II – Mlle Rinaldi]

f) [Variation III – Mlle Gregson]

g) Coda

Acte 3

1) Valse Infernale

2) Pas des Nonnes Damnées

a) Procession des Nonnes [Les Nonnes]

b) Bacchanale [Mlle Draeger / Mlle Nicholson et les Nonnes]

c) Récitatif

d) 1er Air de Ballet – Séduction par l’Ivresse [Les Nonnes]

e) 2me Air de Ballet – Séduction par le Jeu [Mlle Draeger / Mlle Nicholson et les Nonnes]

f) 3me Air de Ballet – Séduction par l’Amour [Mlle Draeger / Mlle Nicholson seule]

g) Choeur Dansé

Ballets revived by Thompson at Covent Garden

- Gli Ugonotti, Meyerbeer (1884)

- Act 3 Ballet

- Fausto, Gounod (1888)

- Act 5 Walpurgisnacht Ballet

- Guglielmo Tell, Rossini (1888)

- Act 1 Pas de Six and Pas d’Archers

- Act 3 Pas de Trois and Pas des Soldats

- Carmen, Bizet (1888)

- Ballet (L’Arlésienne Suite No. 1 (Bizet): Minuetto, Adagietto, Carillon)

- Aida, Verdi (1888)

- Act 2 Ballet

- Roberto il Diavolo, Meyerbeer (1889)

- Act 2 Pas de Cinq

- Act 3 Ballet des Nonnes Damnées

- Esmeralda, Thomas (1890)

- Pas de Deux Valsé (originally composed c. 1865, revived for Marta Draeger)

- Il Profeta, Meyerbeer (1890)

- Act 3 Ballet