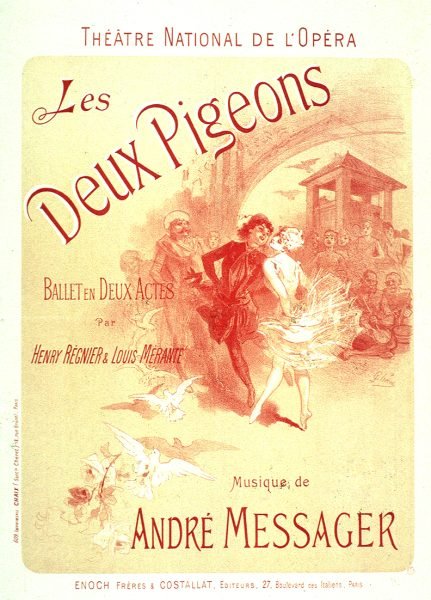

Les Deux Pigeons

Or The Two Pigeons

Ballet pantomime in two acts and three scenes premiered on 18th October 1886 at the Théâtre National de l’Opéra, Paris

Choreography: Louis Mérante

Music: André Messager

Premiers Rôles

Gourouli: Rosita Mauri

Pépio: Marie Sanlaville

Plot

Summary

Acte 1

The principal room in a country house. The interior is rustic, but indicative of ease and comfort. A large window framed in climbing plants overlooks the countryside. Facing the window is a large dove-cot with many pigeons sitting on the roof.

At the rise of the curtain, servants are busy decorating the room with country flowers in honour of their mistress, Mikalia. The youngest of them, roguish by nature, goes from group to group, upsetting everything, borrowing flowers to put in her hair, until, grumbled at by her companions, she goes away sulking.

Discovering a wicker basket she takes a handful of grain which she flings at the pigeons.

Mikalia enters leaning on a stick, for age has robbed her steps of their firmness. The servants greet her with affection and help her to an armchair. Then she asks for her daughter, Gourouli, whom she does not see, nor her daughter’s fiancé, Pépio.

At the same moment the door opens and Gourouli comes in with a bouquet which she offers to her mother, who receives it sadly. Gourouli asks if anything is the matter. She replies that she is worried because Pépio seems moody and dissatisfied. Gourouli is greatly alarmed.

Pépio enters with an air of boredom. Gourouli goes towards him. Pépio pulls himself together, smiles at his fiancée, greets Mikalia, then goes to the window and peers into the distance.

Mikalia urges her daughter to talk to Pépio. So she points out the pigeons which she tells him are happy because they love one another. Inspired by their example they imitate their manners of courtship, then pretend to quarrel and peck each other. Finally, they separate, return, and become friends again.

But Pépio soon grows weary and, sitting down, gives himself up to his day-dreams. Gourouli is disappointed at this abrupt end to their game.

Suddenly strange music is heard and everyone runs to the window. It is a band of gypsies on their way to a neighbouring village. Mikalia bids a servant ask them in, that they may give their performance.

The servants are delighted at the possibility of entertainment and even Pépio seems to cheer up. The troupe gives a number of dances in which Gourouli joins, but her chaste dancing leaves Pépio indifferent. On the other hand he is quite carried away by the fire and attractiveness of the gypsy dances. In fact he is obsessed with the idea to join the troupe.

He informs Gourouli and her mother of his intention to travel. They warn him of the dangers that may befall him. But Pépio announces that if he goes for a few days he will be satisfied. Gourouli agrees and declares that she will accompany him. But Pépio tells her that she must not forsake her mother. Gourouli is about to insist when Mikalia signs to her to give way. So she sits down in desperation while her mother helps Pépio with his preparations.

Ready at last he kisses Gourouli and Mikalia good-bye. A turtle dove coos plaintively and Pépio takes his sweetheart in his arms. Then he departs.

Mikalia bids her daughter follow at a distance and watch over him. Gourouli, accompanied by Stefano, follows on the heels of the traveller.

Acte 2

Scène 1

The sunlit entrance to a village. In the centre is an immense oak-tree which casts a deep shadow. To the left is a gypsy tent; to the right, an inn.

The gypsies are preparing for a festival which is about to begin.

Enter Pépio who is recognised by the band. He enters into conversation with the gypsy girl who had already attracted his attention.

Meanwhile a young girl arrives. She wears a hooded cloak and approaches Zarifi, the chief, who recognises Gourouli. She produces a purse which she offers in return for his aid. He tells her to keep her purse saying that he will be happy to be of service to so charming a girl.

Gourouli reproves him sharply and he asks how he can serve her. She indicates Pépio as her fiancé, saying that he has left her to indulge in adventures, and she wishes him to be sorry for his action and return to her.

“But how can I help?” enquires Zarifi.

“First, by letting that young girl lend me her costume.”

Zarifi consents and tells the gypsy indicated to go with Gourouli into the tent.

At the same moment the village bells ring out, drums beat, and trumpets blare. The villagers enter dressed in their best, with various officials at their head.

Now follows a grand divertissement to which the gypsies contribute dance after dance. But the chief honours fall to Gourouli, who, disguised as a gypsy and dancing with the utmost vivacity, turns the heads of all the men. Even Pépio, failing to recognise her, is carried away by her attractions.

No sooner does Gourouli pause for breath than Pépio is surrounded by gypsies who force him to play cards and lose his all. He has no time to bewail his lot before Gourouli overwhelms him with her gaiety.

However, the sky darkens, rain begins to fall, and everyone hastens to seek shelter before the threatened storm breaks. The gypsies retire into their tent, where Pépio enters in search of Gourouli, only to come face to face with Zarifi, who orders him out. Pépio shudders at having to go out into the rain and tries to gain shelter at the inn, where he is refused admittance as he is penniless.

Pépio, greatly distressed at being unable to find shelter, remembers with regret the warm house he has forsaken. Suddenly he thinks of the oak tree and takes shelter beneath it, but a blinding flash of lightning strips a branch from the tree and Pépio, terrified, runs hither and thither until he falls exhausted to the ground.

Presently the storm abates, the rain stops, and the village children venture out. One of them espies Pépio who, forlorn and wet through, thinks of returning home. The band of imps surround him and assail him with shrill cries. He tries to escape but one boy lassoes him with a cord, and he becomes a butt for their sport.

They pay no heed to his cries for mercy until Stefano comes out of the inn and drives away the children with his stick. Then, hav. ing made certain that their victim is unhurt, he leaves before Pépio has time to thank his deliverer.

Scène 2

Same as Act 1

Mikalia, surrounded by Gourouli’s friends, bewails her deserted home. The young girls vainly strive to console her, but she is full of evil presentiments. Suddenly a girl, who has been looking out of the window, announces that she can see one of the stray birds returning to its nest – Gourouli.

Mikalia rises from her chair and just reaches the door when her daughter enters and embraces her. She tells her that Pépio, too, will soon be back. “Well,” laughs Gourouli, “he has had his lesson, and you will see whether he has profited by it.”

At this juncture Pépio appears on the threshold. He hangs his head, fearing to be received with derision, but, remembering all the kindness he has received, is secretly overjoyed to be back.

Mikalia welcomes him and he melts under her tenderness. He asks whether Gourouli will forgive him. For answer, her mother pushes him towards her daughter who holds him in her arms.

Then the re-united lovers, surrounded by their friends, kneel and receive Mikalia’s blessing.

History

Original Production

Les Deux Pigeons is a ballet originally choreographed in two acts and three scenes by Louis Mérante to a score by André Messager. The libretto by Mérante and Henri de Régnier is based on the fable The Two Pigeons by Jean de La Fontaine. The work was first performed at the Paris Opéra on 18 October 1886.

A writer in La Figaro revealed that when the ballet was first conceived:

“It was the male pigeon which remained at home and the female pigeon which set out in search of adventure. The two roles have since been transposed and this happy change enables us to appreciate Mlle. Mauri under two different aspects, dark or fair, chaste or lascivious, and from this contrast she draws, from the double viewpoint of plastique and choreography, the most unexpected effects.

In the first act the female pigeon is charming without her clouds of muslin and with her fair wig … but this is no more Rosita Mauri. By good fortune we find her again in the second act, with her magnificent black tresses flowing over her shoulders, whose whiteness emerges from a fire-coloured bodice, which gives her an air of diabolical wantonness. In this guise, to a pizzicato which is a near relation of that in Sylvia, she dances an intoxicating variation which, owing to the applause, she has to repeat.”

The rôle of Mikalia was originally to be called Gertrude, but this was changed prior to the première. The premiere cast included Rosita Mauri as Gourouli and Marie Sanlaville as Pépio. In Paris, the rôle of Pépio continued to be danced by a woman until 1942.

The score was dedicated to Camille Saint-Saëns, whose influence helped gain Messager the commission for the ballet, following three ballets which the younger composer had written for the Folies Bergère, Fleur d’oranger, Vins de France and Odeurs et Parfums. Les Deux Pigeons was first premièred after a performance of Donizetti’s La Favorite.

Selected Revivals

21 June 1906

Location: His Majesty’s Theatre, London

Staged by François Ambroisiny to an abridged version of the score edited by Messager himself. Messager also conducted the première.

Messager was the musical director at the Royal Opera House from 1901 to 1906. Though his ballet had been staged by Hague in 1898, he expressed a wish to see it again revived. This suggestion was opposed by Hague, who did not fondly remember the 1898 staging with its quarrels with Nicholson and its lukewarm reception by the audience and critics. Hague successfully managed to convince the Covent Garden management to oppose such a revival, and so Hague was permitted to proceed with the revival of Naïla as planned.

Messager was greatly irritated by this development, and so sought to have his ballet staged elsewhere. He was able to convince His Majesty’s Theatre to stage the ballet, and Ambroisiny was selected to provide the choreography. Ambroisiny was concurrently the balletmaster of the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels and occasionally choreographed ballets at His Majesty’s, notably his ballet The Fallen Star which had premiered there 1903 to good reviews. The production was better received than the 1898 Covent Garden production, though it was not again revived following its 1906 run.

1912

Location: Théâtre National de l’Opéra, Paris

Staging of the abridged London version.

1919

Location: Théâtre National de l’Opéra, Paris

Staging of a one-act version by Albert Aveline.

London Revivals

1898 Revival

In 1898 the ballet was revived in London by Richard Hague for Sarah Nicholson under the title of The Two Pigeons.

The ballet’s path to creation was not smooth, primarily due to the mutual dislike between Nicholson and Hague. Nicholson was not fond of the choreography that Hague provided for her, and Hague was unmoved by the vast majority of Nicholson’s pleas, requests or suggestions.

A large source of disagreement was with the choreography of the first act. Hague, aiming to increase the dramatic arc of the rôle, gave Nicholson more subdued steps for the first act and more spirited steps for the second, to highlight the contrast and Gourouli’s transformation into a gypsy. This had the result, at least according to Nicholson, of making her appear diminished in the first act, and especially so beside Djali, portrayed by Giulia Moretti. Nicholson was particularly unsatisfied with her choreography for the Thème Varié in the first act, where she felt that Moretti’s variation eclipsed her own. Hague did not wish to change this, as he believed that such a dynamic shifted the focus of Pépio and the audience to Djali, explaining Pépio’s departure.

Hague also included students of the Royal Ballet School to play the children in the first scene of the second act.

The production was not a great success, and both Nicholson and Hague blamed each other for the failure of the work. Critics generally shared the opinion that the second act was stronger than the first, with several making statements to the effect that Moretti’s performance was the sole highlight of the first act. Of the second act critics were more complementary, with Nicholson being praised for her Variation in the Grand Pas des Tziganes, the same variation that Mauri had been praised for at the 1886 première.

Rôles

Gourouli: Sarah Nicholson

Pépio: Antoine Férat

Djali: Giulia Moretti

Zarifi: James Elton

Musical Revisions

Few musical revisions were made by Auguste Péchard, save for a variation being composed for Moretti as Djali in the Grand Pas de Tziganes. However, this variation was eventually cut by Hague during the rehearsal process, as he decided that the variation interrupted Pépio’s fascination with the disguised Gourouli.

Résumé des Scènes et Danses

Acte 1

1) Introduction

2) Scène Première

3) Entrée de Mikalia

4) Entrée de Pépio

5) Pas des Deux Pigeons

6) Scène

7) Entrée des Tziganes

8) Petite Scène

9) Thème Varié

a) Thème

b) Variation I – Gourouli et les coryphées

c) Variation II – Djali

d) Coda

10) Scène Finale

Acte 2

Scène 1

11) Prélude

12) Scène

Divertissement

13) Danse Hongroise

14) Grand Pas des Tziganes

a) Entrée

b) Andante

c) Valse

d) Variation de Djali

e) Variation de Pépio

f) Variation de Gourouli

g) Coda

15) Orage

16) Scène des Enfants

Scène 2

17) Scène Finale – Le Retour