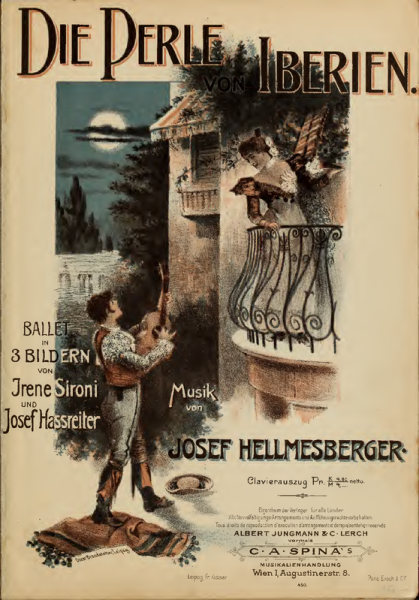

La Perle d'Ibérie

Or The Pearl of Iberia

Ballet pantomime in two acts and three scenes premiered in 1902 at the Wiener Hofoper, Vienna

Choreography: Joseph Hassreiter

Music: Joseph Hellmesberger Jr.

Libretto: Irene Sironi

Plot

Summary

Acte 1

Scène 1

A town square

People go about their way. There is a singer who serenades some young ladies. One of the guards tries to put a stop to this, chasing the singer through the square but he evades him.

The wealthy students enter the square, having finished their lessons for the day. They buy food and drink as well as pay court to the beautiful women. One among them is Roberto, who seems preoccupied. His friends mock him but he states he is in love with only one, the beautiful gypsy Patricia.

Patricia enters and spies her love Roberto, the pair embrace.

The students and gypsies dance.

The approach of horsemen is heard. Don Ramiro, their captain, proclaims that the Queen has lost a pearl, her prized pearl from her crown and there is to be a reward for whoever finds it.

Patricia recognises Don Ramiro and hides from him with Roberto. However, Don Ramiro spots her and bids her dance, threatening Patricia’s grandmother, Fatima, to make her do so. She complies and exits soon after.

Don Ramiro conjures a plan with his henchman, Luis. He produces the pearl, throws it in the Ebro, saying he will blame the gypsies for their disappearance and thus will coerce Patricia to accept his advances to free them. They leave.

Patricia re-enters to find Fatima, who warns her of the coming danger. Don Ramiro enters with his entourage and decries that it is Fatima who has stolen the pearl. He, aside, tells Patricia that if she does not submit to him he will ensure Fatima perishes, but if she does everyone will be spared. Patricia refuses and mistress throws herself into the Ebro and Fatima and the other gypsies are captured.

Scène 2

An underwater grotto

Patricia sinks to the depths of the Ebro where she is welcomed by Tritons and Undines.

The Spirit of the Ebro shows her his treasures as well as the royal pearl that is said to have been stolen by the gypsies. As thanks for his help, the Ebro bids Patricia to dance and she obliges.

The Ebro presents the pearl to Patricia and asks her to climb into the shell. The shell rises bearing Patricia to the surface.

Acte 2

In front of a church in Zaragoza

The crowd strolls and sellers peddle their wares.

Don Ramiro enters with Luis, looking for Patricia, once they cannot find her he leaves.

Actors and dancers perform for the crowds and try to collect money.

The church bells sound and the Queen with her retinue emerges from the church and walks to the throne. Don Ramiro confirms that the Queen’s lost pearl is due to the gypsies and the death sentence is passed. The gypsies, Fatima among them, are led in and the pyre is lit.

Roberto enters with the students and tries to stop the proceedings but is captured. Right as Don Ramiro is to include him in the execution, the Ebro begins to rise. Patricia rises from the waters as the Ebro extinguishes the pyre. Paquita accuses Don Ramiro before the Queen, handing her the stolen pearl. Don Ramiro falls from grace and is arrested and the Queen pardons the gypsies and reunites Patricia and Roberto.

All dance in celebration.

History

Original Production

La Perle d’Ibérie originally premièred as Die Perle von Iberien as a ballet in three scenes. Premiering in Vienna in 1902, it was, as most of the Viennese ballets were, initially well received but quickly forgotten after its initial run and its airs relegated to filling drawing room music books.

London Revivals

1912 Revival

In 1912 Richard Hague was persuaded to revive the ballet by Jane Wheaton, a première danseuse with the troupe, for her benefit. Hague thought the scenario ridiculous and music uninspiring but nevertheless allowed himself to be persuaded to revive the ballet for Wheaton, reviving the ballet as The Pearl of Iberia.

Though Hague retained some elements of the original plot, he made large alterations to expand the danseuse’s rôle and improve the flow and cohesion of the plot.

The musical revisions were undertaken by Laurence Selwood, who expanded and supplemented Hellmesberger’s score. Hague requested numerous revisions to what he considered a lacking score, resulting in a score that was arguably the most extensive that he ever revised (save for the 1906 abridgement of Naïla).

One of the largest issues that Hague had with the score was the continuous repetition of one theme that permeated every scene of the ballet. Hague is quoted as having said:

“Hellmesberger wrote but one theme and decided that one was enough”

Wheaton, on the other hand, was more appreciative of the use of leitmotif. Hague took it upon himself (with Selwood’s assistance) to expunge some of the repetitions of the theme in favour of other music, but others were retained or indeed reinstated at Wheaton’s instance.

As part of these revisions, Selwood orchestrated Péchard’s 1899 Pymalion Grand Pas Classique, as Péchard only left the pas in orchestral sketches (due to the pas being cut before its première). Selwood’s orchestration, though more modern than what Péchard would have done, was nevertheless well received.

The plot was revised and made more coherent and the names of the main characters were also changed; Paquita became Patricia and Piquillo became Roberto. This change was principally to avoid comparisons to the popular production of Deldevez’s Paquita that was in the repertory of their rival troupe at His Majesty’s Theatre.

The ballet was not particularly well received, as many critics shared Hague’s concerns about the ridiculous plot (which included the heroine descending to the bottom of the Ebro river, retrieving the Queen’s stolen pearl from the Spirit of the Ebro and the Ebro overflowing its banks to save some gypsies who were set to be burnt at the stake).

Despite the lukewarm reception, Wheaton’s dancing was praised and Hague’s choreography was found to be “adequate, though not particularly remarkable”. Some critics lamented Wheaton’s choice of send off, believing she could and should have chosen a more worthy ballet. The only successes to come out of the ballet were two of the waltzes: the Hellmesberger’s Waltz of the Undines of the second scene of the first act was well received and made it into ballrooms and salon sheet music; while Péchard’s waltz in Selwood’s orchestration in the Grand Pas Classique of the second act enjoyed a brief period of popularity before fading from fashionable memory.

The ballet was later revived in 1967 with new choreography by Sir Frederick Ashton but was performed for the last time in 1972. It has not since been revived, but a single variation from the Pas des Undines was set and demonstrated in an evening titled Lost Works of Sir Frederick Ashton.

Rôles

Patricia: Jane Wheaton

Musical Revisions

To support the revised plot, Selwood undertook an extensive revision of the score, arguably the most revised score that Hague ever choreographed to. Several of the reprises of the Valse Espagnole were expunged (as Hague found the constant reference to the theme tiresome) and Selwood composed new music to support the newly created scenes and dances.

As the ballet had no grand pas in the second act for Wheaton, Hague felt it necessary to add one. He toyed with the idea of commissioning a new pas or reviving the Pas Robert, but instead settled on the interpolation of a Grand Pas Classique that Péchard had composed for the 1899 revival of Pygmalion that was discarded before its première in favour of the original pas. The Pas Robert was added to The Fairy Doll (which was also revived in 1912 and in which Wheaton also danced).

Selwood, though relatively faithful to Péchard’s sketches, did not seek to orchestrate the pas as Péchard would have done. He orchestrated the pas in a manner more suited to 1912 than 1899, evidenced by Selwood’s use of the saxophone. Saxophones were not unheard of in ballet (Delibes had included saxophones in his 1876 score for Sylvia) but allegedly neither Thompson nor Péchard were fond of them. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that Thompson’s early revivals of Sylvia (1886 and 1888) rescored the ballet to exclude the saxophones, but by the time Draeger was dancing the rôle in 1892 the saxophones were firmly back in the score.

Selwood discarded Péchard’s note to give the melody of the Adage to a clarinet, instead giving it to a solo saxophone. This required some reworking of the music: the opening cadenza was rewritten to be more idiomatic to the instrument, the melody was slightly edited to stay within the saxophone’s natural range and the key of the Adage was changed from A major to A flat major (the only part of the pas to be in a flat key, the other numbers being in the sharp keys of G, D, A and E major).

Selwood also added countermelodies not found in Péchard’s sketches (though this change was less discussed, due to the possibility that Péchard might have added those during the orchestration process and only sketched the outlines of the numbers). Additionally, one of the variations was cut from the pas, leaving four variations (two for female sujets and one each for Patricia and Roberto). Despite Selwood’s changes, the pas was nonetheless well enough received.

The Grand Pas Classique was meant to replace the original Pas de Deux of the third act and was composed at Nicholson’s request. To make room for the new pas the Danse des Prêtresses de Vénus, the Valse des Colombes and the Pas de Trois des Grâces were cut. However, when the theatre manager heard about this development, he actively blocked the inclusion of this new pas. Nicholson of course was furious with being countermanded and walked out of the ballet. The theatre manager (who incidentally did not much like Nicholson) pressed for her replacement. The stalemate continued as a new danseuse, Harriet Linwood, stepped in to learn the rôle of Galatée with the original version of the third act divertissement restored. Eventually Nicholson relented, stepping back into the rôle and allowing the Grand Pas Classique to be removed. She would still share the rôle with the second danseuse, and the run was extended to account for the dual casting.

Résumé des Scènes et Danses

Acte 1

Scène 1

1) Introduction

2) Scène Première

3) Scène – Entrée de Patricia

4) Scène Dansante – Habanera

5) Danse Tzigane

6) Valse Espagnole

7) Scène – Entrée de Don Ramiro

8) Danse de Patricia

9) Scène – Don Ramiro

10) Scène Finale – Rentrée de Patricia

Scène 2

11) Entr’acte

12) Scène Sous-Marine

13) Pas des Undines

a) Valse des Undines

b) Adage

c) Variation I

d) Variation II

e) Variation III – Patricia

f) Coda (Valse-Galop)

14) Scène Finale

Acte 2

15) Entr’acte

16) Scène Première

17) Ballabile des Artistes de Rue

a) Les Danseurs

b) Les Acteurs

c) Les Femmes

d) Coda

18) Marche – Entrée de la Reine

19) Scène Dramatique

Divertissement

20) Boléro

21) Cachucha

22) Espagnole

23) Grand Pas Classique (Péchard, orchestrated by Selwood)

a) Valse

b) Adage

c) Variation I

d) Variation II – Pizzicato

e) Variation III – Roberto

f) Variation IV – Patricia

g) Coda

24) Danse Finale (expansion of Hellmesberger’s score)

25) Apothéose