Le Diable à Quatre

Or The Devil to Pay

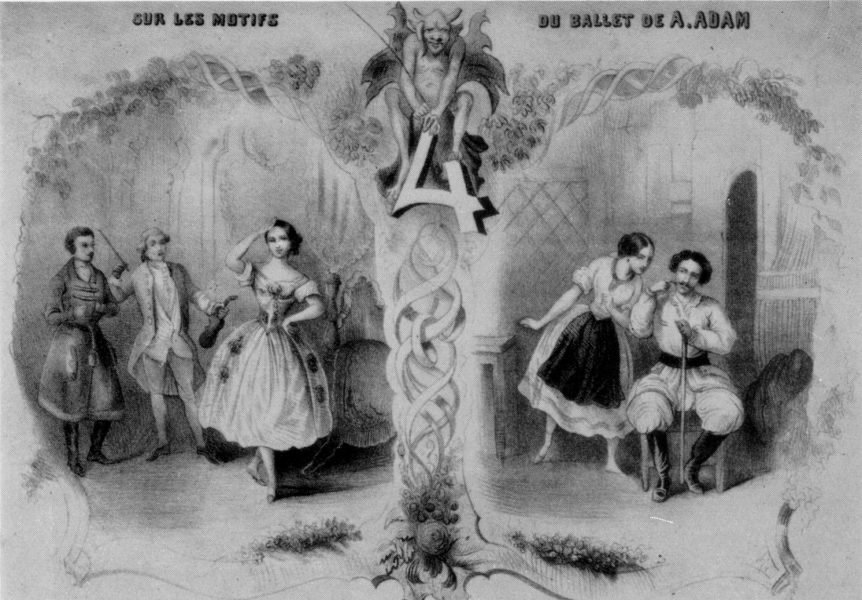

Ballet pantomime in three acts and four scenes premiered on 11th August 1845 at the Théâtre de l’Académie Royale de Musique, Paris

Choreography: Joseph Mazilier

Music: Adolphe Adam

Premiers Rôles

Mazourka: Carlotta Grisi

Comte Polinski: Lucien Petipa

Comtesse: Maria Jacob (known as Mlle Maria)

Mazourki: Joseph Mazilier

Plot

The plot is based on an English farce of the same title and contrasts the lives of two Polish women, a spoilt Countess and Mazourka, a sweet-tempered woman who is married to a brutal basket-maker called Mazourki. The two women encounter a magician disguised as a blind fiddler. The Countess behaves offensively but Mazourka is kind and in return he causes them to change places for a day. Mazourka astonishes everybody at the Countess’s castle with her unexpected kindness while the Countess has to suffer Mazourki’s rough treatment. Chastened, she promises to behave more humanely when returned to her real life, while Mazourki promises never to beat his wife again.

Summary

Acte 1

The scene represents a lawn before the castle of Count Polinski. On the left hand side is the entrance to the castle. On the same side is a pavilion belonging to the castle, with a window in front of the stage. On the right hand side there is a small cabin, where dwells a basket maker; a window is opened also in front. The background is a luxuriating landscape.

Gamekeepers celebrate the Count’s generosity, and Yvan, the castle doorkeeper, joyfully announces his engagement to Yelva, the Countess’s chambermaid. The Count warmly blesses the match, even providing a dowry, and permits a wedding dance to take place during the hunt.

Festivities are abruptly disrupted when the Countess, furious at being neglected for hunting and social pleasures, storms in before the guests. In a public and humiliating scene, she accuses the Count and his friends of abandoning her. To everyone’s surprise, Polinski asserts his authority, insisting the hunt proceed and announcing a ball for the following day, forcing the Countess to retreat in shock and anger.

Meanwhile, attention shifts to Mazourka, a lively basket-maker’s wife, and her husband Mazourki, whose passions clash: she loves dancing, he loves drink. After a comic attempt at mutual restraint, both abandon self-control and indulge freely.

The village gathers for Yvan and Yelva’s wedding celebration. Mazourka dances joyfully to the music of a blind fiddler, delighting the Count and his guests. Suddenly, the Countess reappears, enraged that festivities continue without her consent. In a violent outburst, she smashes the blind man’s violin, scattering the villagers and guests and bringing the fête to ruin.

Once the Countess departs, Mazourka consoles the blind fiddler, who reveals himself to be a magician. He foretells that Mazourka may become a great lady for one day, while the Countess will take her place in the hut. Though skeptical, Mazourka ultimately agrees.

As night falls, the magician summons spirits, and a magical exchange occurs: Mazourka is transformed into the Countess and carried into the castle whereas the Countess is dressed as a peasant and taken to Mazourka’s hut.

Acte 2

Scène 1

The scene represents the inside of the basketmaker’s hut. On the background a window opened, through which the country is seen. On the right hand side a rustic be surrounded by curtains of green serge. On the left hand side a table covered with baskets not yet finished, and bottles, benches and chairs.

At dawn, Mazourki awakens to find his “wife” behaving very strangely. The Countess, now trapped in Mazourka’s life, is horrified by her surroundings and outraged by Mazourki’s rough familiarity. He, believing her mad, treats her with increasing authority and violence.

When Yvan and Yelva arrive to invite the couple to their wedding, the Countess tries desperately to assert her true identity, but the servants dismiss her as insane. Her behavior only confirms Mazourki’s suspicions, and he subjects her to humiliation, forced reconciliation, and even compels her to dance for his amusement.

Seizing an opportunity while Mazourki attires himself for the wedding, the Countess escapes the hut, with Mazourki chasing after her.

Scène 2

The scene represents the inside of an elegant boudoir in the castle; with a divan, toilette, chairs, etc.

In the castle, Mazourka awakens as the Countess, surrounded by luxury. The magician reminds her that she must fully assume the role. Though initially awkward, Mazourka’s natural kindness astonishes the servants, especially Yelva, whom she treats with warmth rather than cruelty.

When the Count arrives, he is amazed by his wife’s gentleness and generosity. He attempts to court her affection, but Mazourka firmly refuses intimacy, remaining faithful to Mazourki. Instead of angering the Count, this sincerity puzzles and softens him.

Preparations begin for the grand ball. Mazourka struggles with the aristocratic dancing as instructed by the dancing master, revealing her peasant origins until the magician discreetly intervenes. Instantly transformed, she dances with elegance and brilliance, enchanting the Count and domestics alike.

Acte 3

The scene represents a rich gallery forming a hothouse, profusely adorned with various rare plants.

The Count receives the guests with Mazourka as the Countess. There are dances for the amusement of the guests.

During the ball, the true Countess bursts in, still dressed as a peasant and furious at seeing another woman in her place. Chaos ensues as Mazourki arrives, insisting the peasant woman is his wife, while the Countess claims to be mistress of the château. Guests laugh, believing her mad.

Mazourka intervenes with compassion. She forces Mazourki to swear an oath to abandon drink and treat his wife kindly, then consoles the Countess, urging her to repent her former cruelty.

The Countess, broken and remorseful, accepts her fall as divine punishment and begs forgiveness. At the climactic moment, Mazourka appeals to the magician, who restores everyone to their rightful place: the Countess regains her rank and Mazourka returns to her humble life, content and loved.

The Countess, transformed by the ordeal, embraces Mazourka and promises to live with humility and kindness. There is universal reconciliation and a joyful final dance.

History

Original Production

Le Diable à Quatre was originally choreographed in two acts and four scenes for the great Carlotta Grisi. The ballet’s simple comic realism, rare during the Romantic era, was warmly praised, and gave Grisi the opportunity to display a sparkling wit, rather than her usual poetic lyricism.

In 1883 Thompson revived the ballet for Marguerite Lemoine under the title of The Devil to Pay (the same title would be used for subsequent London revivals of the ballet). The production was so successful that Lemoine chose to dance the ballet for her benefit performance the following year as she was to retire at the end of the 1884 season.

Selected Revivals

26 December 1845

Location: Théâtre Royale de Bruxelles, Brussels

Staged for Mlle Rousset.

27 December [O.S. 15 December] 1846

Location: Imperial Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow

Staged by Ekaterina Sankovskaya.

28 October 1846

Location: Grand Theatre, Warsaw

Staged by Roman Turczynowicz for Konstancja Turczynowicz under the title of Hrabina i wieśniaczka (The Countess and the Peasant) with Józef Stefani revising the score. Mazourki in this production (called Maturyn) was danced by Felix Kschessinsky who would go on to dance with the Imperial Ballet under Petipa and was the father of the Prima Ballerina Assoluta Matilda Kschessinskaya.

18 July 1848

Location: The Broadway Theatre, New York

Staged by M Bartholomin and M Montplaisir for Mme Montplaisir.

26 November [O.S. 14 November] 1850

Location: Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, St Petersburg

Staged by Jules Perrot under the title of La Femme Capricieuse with extensive musical revisions by Pugni that expanded the ballet from a ballet pantomime in two acts and four scenes to a grand ballet in four acts.

24 March 1851

Location: Théâtre de l’Académie Nationale de Musique, Paris

Staged for Marie-Adeline Plunkett with Lucien Petipa as the Comte.

24 March 1862

Location: Théâtre Impérial de l’Opéra, Paris

Staged by Marius Petipa for his first wife, Mariia Surovshchikova-Petipa. Also sharing the stage were Lucien Petipa as the Comte and Zina Mérante (wife of the famous dancer and choreographer Louis Mérante) as the Comtesse.

The score was revised by Cesare Pugni, who composed two new pas for Mme Petipa. The first of these pas was dubbed the Pas Nouveau and replaced Adam’s original Pas de Neuf in the first act. The Pas Nouveau was danced by Mme Petipa and four female coryphées and was choreographed by Marius Petipa.

The second of these pas was the celebrated Polski Mazur, composed to replace the Grand Pas de Deux Noble of the second act. The Polski Mazur was danced by Mme Petipa’s Mazourka partnered by a male dancer specially engaged from St. Petersburg (at what was noted as a large salary for a male dancer), Felix Ivanovitch Kschessinsky. The Polski Mazur was well received at its première, so much so that it was encored.

Kschessinsky had also danced the rôle of Mazourki (called Maturyn) in the 1846 Warsaw staging of the ballet.

4th February [O.S. 23rd January] 1885

Location: Imperial Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, St Petersburg

Staged by Petipa for Eugenia Sokolova partnered by Pavel Gerdt. Ludwig Minkus revised the score in Pugni’s four act version.

London Revivals

1883 Revival

In 1883 Thompson revived the ballet in two acts and four scenes for Lemoine as the heroine Mazourka. The score was revised by François Bardet and as usual Thompson remained faithful to the original libretto but re-choreographed several of the dances.

Grisi’s first act pas (which she danced with eight female coryphées) was given no name by Adam in the score, simply being referred to as the Pas Seul in the programmes. Thompson wished to rename the pas for clarity, as due to the presence of the coryphées it was not, strictly speaking, a Pas Seul. He first considered renaming the pas as the Pas de Neuf, before settling on the Pas de Grisi in Grisi’s honour.

The function of the Pas de Deux titled La Varsovienne was altered. At the ballet’s première the pas had been danced by Grisi and Petipa. The couple had also danced the Grand Pas de Deux Noble, but they had danced this pas in the second scene of the second act, not the third scene. However, Thompson moved the Grand Pas de Deux Noble from the lesson scene to the ballroom scene (i.e. from Act 2, Scene 2 to Act 2, Scene 3) and gave La Varsovienne to two sujets in the ballroom scene, newly created characters named the Ambassador and Ambassadress.

Rôles

Mazourka: Marguerite Lemoine

Comte: Johann Faber

Comtesse: Emma Ashfield

Ambassadress in La Varsovienne: Mary Butler

Ambassador in La Varsovienne: Rafael Caravetti

Musical Revisions

The Entr’acte of the third scene of the second act was expanded to allow for more time for the guests to enter the ballroom and interact with each other.

A new variation was written for Mary Butler as the Ambassadress in the Pas de Deux titled La Varsovienne of the third scene of the second act, replacing Adam’s original variation. Butler had joined the troupe at the beginning of the 1883 season as a sujet.

Both the Comte and Mazourka received brand new variations for the Grand Pas de Deux Noble of the third scene of the second act, replacing Adam’s original variations.

As the corps de ballet did not have much dancing to do in the second act, a Cracovienne Générale was added for the troupe, in which the corps de ballet, sujets and main characters participated.

Extract from the Cracovienne Générale, composed by François Bardet (1883)

Résumé des Scènes et Danses

Acte 1

1) Introduction

2) Scène Première – Les Veneurs et Gardes de Chasse

3) Scène – Entrée d’Yvan et Yelva

4) Scène – Entrée du Comte

5) Scène – Le Partie de Chasse

6) Scène – Entrée d’Yelva

7) Scène – Entrée de la Comtesse

8) Scène – Entrée de Mazourka

9) Scène – Les Paysans

10) Scène – Les Nobles

Divertissement

11) Pas de Trois

a) Entrée

b) Variation I

c) Variation II – Yvan

d) Variation III – Yelva

e) Coda

12) Pas de Grisi

a) Andante

b) Allegretto non troppo

c) Variation de Mazourka

d) Coda

13) Mazourka

14) Scène – La Colère de la Comtesse

15) Scène – Mazourka et l’Aveugle

16) Scène Finale – La Transformation

Acte 2

Scène 1

17) Entr’acte et Scène Première – La Cabane du Vannier

18) Scène – Entrée d’Yvan et Yelva

19) Scène de La Dispute

20) Polka à Coup de Bâton

21) La Toilette de Mazourki

Scène 2

22) Entr’acte et Scène – Mazourka et Le Magicien

23) Scène – Le Toilette de Mazourka

24) Scène – Entrée du Comte

25) Scène – La Leçon de Danse

26) Scène Finale

Scène 3

27) Entr’acte et Scène du Bal (expanded)

28) Scène – Les Invités

Divertissement

29) Pas de Fantaisie

a) Andante

b) Allegretto

c) Variation à Deux

d) Coda-Valse

30) La Varsovienne – Pas de Deux

a) Entrée

b) Adage

c) Variation I

d) Variation II (for Miss Butler)

e) Coda

31) Grand Pas de Deux Noble

a) Adage

b) Allegretto

c) Variation du Comte

d) Variation de Mazourka

e) Coda

32) Scène – Entrée de la Comtesse

33) Scène Dramatique

34) Cracovienne Générale

35) Scène Finale

1884 Revival

In 1884 Lemoine requested to dance the ballet for her benefit as she was to retire at the end of the 1884 season. She was granted this request and so the ballet was restaged for her. Thompson did not make significant changes to the ballet, save the shortening of a couple of scenes to improve the pacing of the narrative.

Lemoine did not end up dancing all the performances in the rôle, but decided to leave London a month earlier than scheduled to return to France on urgent business. Before she left, Lemoine proposed Ashfield, rather than Velluti take on the remainder of her performances (numbering three), citing Ashfield’s success as the Marchesa in the previous year’s revival of Marco Spada. Thompson decided to go ahead and cast Ashfield in the rôle with Faber as her partner, and she received good reviews for her portrayal of Mazourka.

Rôles

Mazourka: Marguerite Lemoine / Emma Ashfield

Comte: Johann Faber

Comtesse: Emma Ashfield

Yelva: Mary Butler

Yvan: Rafael Caravetti

1894 Revival

In 1894 Thompson revived the ballet for the benefit of Marta Draeger with musical revisions by Auguste Péchard.

In late 1893 Draeger decided that she wished to retire from the stage. She considered her 1893 role as Galatée in Pygmalion to be her crowning glory and so wished to end her career on a high note. However, neither the theatre managers nor Thompson wished her to retire as she was far too popular. A compromise was to be made, Draeger would dance one final season on the London stage in 1894. The theatre director offered to have a new ballet created for her but she refused, choosing instead to dance in Esmeralda for her benefit, a ballet which had not been staged in London since 1878. Thompson also revived The Devil to Pay for her in the same season, a ballet that had not been staged in London since 1884.

Unfortunately, Draeger’s stay in London did not turn out to be a completely pleasant one. She was particularly disliked by Sarah Nicholson, an English ballerina who was a rising star in the troupe. Nicholson had been the one to understudy the roles of Draeger and had created the role of the Queen of Hearts in the 1890 ballet Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The same year she shared the role of Lise in The Wayward Daughter with Draeger and their rivalry increased. Nicholson danced the role of Julie alongside Draeger as Béatrix in the 1891 revival of The Beauty of Ghent as well as reprising her role as the Queen of Hearts in the same year.

However, Nicholson kicked up her largest fuss in the 1894 revival of The Devil to Pay where she had been cast as the Comtesse. Though it was the second ballerina role she was unsatisfied with the amount of dancing she was to be given in the ballet. To soothe her anger, Thompson commissioned the expansion of the second act Polka à Coup de Bâton (the rôle’s only real pas), lengthening the dance and re-choreographing the number in a more elaborate fashion to display her talents.

Nicholson was further irritated when she heard that a brand new pas the Pas de Leçon would be composed for the second act for Draeger. The final blow came when Harriet Linwood, the danseuse who had been cast as Yelva succeeded in having a Pas de Deux inserted into the first act for her in place of the original Pas de Trois. Nicholson was so insulted that a lesser soloist should receive a new pas while she did not that she walked out of the ballet, refusing to attend rehearsals for two weeks. To entice her to return, the theatre manager promised her a pas of her own. Thompson begrudgingly complied with this request, expanding further on the Polka à Coup de Bâton into the Pas Villageois which was danced by Mazourki and the Comtesse in the first scene of the second act. In addition to this, Thompson was also obliged to arrange a Pas Seul for her in the third act.

Despite all the backstage drama the revival would turn out to be a great success with Draeger receiving great praise in the rôle of Mazourka. Draeger’s performances as Mazourka would lead to the rôle becoming one of the most coveted amongst the danseuses of Covent Garden.

Rôles

Mazourka: Marta Draeger

Comte: Frederick Hale

Comtesse: Sarah Nicholson

Yelva: Harriet Linwood

Ambassadress in La Varsovienne: Vittoria Riccardi

Musical Revisions

The ballet was expanded from two acts and four scenes to three acts and four scenes. Act 2, Scene 3 became the third act, while Act 2, Scene 1 and Act 2, Scene 2 retained their original numberings.

The original Pas de Trois which was danced by Yelva, Yvan and an additional unnamed danseuse was replaced by a Pas de Deux for Yelva and Yvan. This was in no small part due to Harriet Linwood, the danseuse who had been cast in the rôle of Yelva. She pressed for a new Pas de Deux to be arranged for her but Thompson did not wish to do so, preferring to retain Adam’s original Pas de Trois. However, Linwood was the mistress of The Earl of Banstead, a wealthy aristocrat whose father, the Marquess of Athelington, was one of Covent Garden’s patrons. She used her influence to get her way and so Thompson was obliged to arrange a new Pas de Deux for her. Péchard arranged the music for the new pas, and at Thompson’s request several of the numbers were taken from Adam’s original Pas de Trois. The Entrée, Variation d’Yvan and Coda were taken from Adam’s original Pas de Trois while the Adage and Variation d’Yelva were newly composed.

Variation for Miss Linwood as Yelva in the Pas de Deux, composed by Auguste Péchard (1894)

A new variation was added for Mazourka in the Pas de Grisi. This was a supplemental variation originally written for Fleur de Lys in the Grand Pas des Corbeilles in the 1878 revival of Esmeralda.

The Polka à Coup de Bâton of the first scene of the second act was expanded into the Pas Villageois. This expansion was a result of Nicholson’s requests, who complained about how little dancing she was given. The pas followed the story at that point, where Mazourki ordered the Comtesse (who through magic had been transformed to look like his wife Mazourka) to dance. She began by dancing a noble Menuet which he quickly grew bored of. He then showed her (with the help of stick he beat on the ground) how to dance in a more ‘rustic’ and entertaining style. The pas concluded with a rousing finale, including big lifts and a difficult diagonal for the Comtesse that consisted of several repeated quick relevés sur la pointe.

As the second act was split into two a new grand pas was needed for the act. This resulted in the celebrated Pas de Leçon being added to the second scene of the second act. The pas builds on the action of the scene where Mazourka is being taught how to dance in the ‘noble’ style. The pas was arranged as a Pas de Six danced by Mazourka, the dancing master and four female coryphées as chambermaids. The Comte, though present, did not dance but observed the proceedings from his seat to the side of the stage. The pas, true to its name, served as a rehearsal and educational exercise for Mazourka. It featured passages of academic and almost pedagogical choreography, repeated as the dancing master assessed his pupil’s progress and technique. In this way, Draeger was also able to display her technical precision and exactness as well as her command of technique and pointework. Her variation, in particular, was technically challenging, including double pirouettes en attitude and a diagonal of temps levés sur la pointe. Another notable feature of this pas was the prominent use of the harp. A harp cadenza preceded the Adage and Mazourka’s variation was also set to harp music. This musical choice was specifically requested by the theatre director, who wished to show off the talents of Friedrich Mandl, a talented Prussian harpist that had been engaged earlier that year as harpist in the Covent Garden orchestra. Mazourka’s variation in particular became a highlight of the ballet, with the variation even being encored at its premiere.

A new polonaise rhythm variation was composed for the Ambassadress in La Varsovienne. This variation was composed for Vittoria Riccardi, a visiting Italian danseuse and replaced the supplemental variation added in 1883. Though polonaise variations had by then largely fallen out of fashion, Riccardi specifically requested it. Thompson and Péchard were compelled to comply as the management wanted to feature her on the Covent Garden stage while she was in London. The variation was not retained for subsequent revivals of the ballet, and the variation that was written for the 1883 revival (a more conventional waltz variation) was restored soon after Riccardi’s departure.

Variation for Miss Rinaldi as the Ambassadress in La Varsovienne, composed by Auguste Péchard (1894)

A new variation was also composed for Draeger in the Grand Pas de Deux Noble of the third act. Originally, this was to be the only change to the pas, with her partner dancing the 1883 variation instead of Adam’s original variation. However, at the last minute Draeger requested to substitute the pas for the Pas de Deux that had been written for her 1888 performances as the titular character in Giselle. She wished to include the pas as an homage to her earlier days at Covent Garden as it was a rôle she looked back on with fondness. The newly composed variation was retained and was interpolated into the Giselle pas.

A Pas Seul was arranged for Nicholson as the Comtesse in to placate her. The pas was danced before the Cracovienne Générale of the third act. Thompson expressed that he did not like the positioning of the pas as he felt that it greatly detracted from the flow of the story. However, subsequent danseuses who performed the rôle greatly appreciated this pas (being the rôle’s only real piece of solo dancing) and refused to let it be removed from the ballet.

Résumé des Scènes et Danses

Acte 1

1) Introduction

2) Scène Première – Les Veneurs et Gardes de Chasse

3) Scène – Entrée d’Yvan et Yelva

4) Scène – Entrée du Comte

5) Scène – Le Partie de Chasse

6) Scène – Entrée d’Yelva

7) Scène – Entrée de la Comtesse

8) Scène – Entrée de Mazourka

9) Scène – Les Paysans

10) Scène – Les Nobles

Divertissement

11) Pas de Deux

a) Entrée (original Adam, arranged)

b) Adage (newly written)

c) Variation d’Yvan (original Adam, arranged)

d) Variation d’Yelva (newly written for Miss Linwood)

e) Coda (original Adam, arranged)

12) Pas de Grisi

a) Andante

b) Allegro non troppo

c) Variation de Mazourka (supplemental variation for Fleur de Lys in the Grand Pas des Corbeilles in the 1878 revival of Esmeralda)

d) Coda

13) Mazourka

14) Scène – La Colère de la Comtesse

15) Scène – Mazourka et l’Aveugle

16) Scène Finale – La Transformation

Acte 2

Scène 1

17) Entr’acte et Scène Première – La Cabane du Vannier

18) Scène – Entrée d’Yvan et Yelva

19) Scène de La Dispute

20) Pas Villageois

a) Menuet

b) Polka à Coup de Bâton (expansion of Adam’s original music)

c) Coda – Louré (expansion of Adam’s original music)

21) La Toilette de Mazourki

Scène 2

22) Entr’acte et Scène – Mazourka et Le Magicien

23) Scène – Le Toilette de Mazourka

24) Scène – Entrée du Comte

25) Scène – La Leçon de Danse

26) Pas de Leçon

a) Adage

b) Allegretto

c) Variation du Maître à Danser

d) Variation de Mazourka

e) Coda

27) Scène Finale

Acte 3

28) Entr’acte et Scène du Bal (expanded 1883)

29) Scène – Les Invités

Divertissement

30) Pas de Fantaisie

a) Andante

b) Allegretto

c) Variation à Deux

d) Coda-Valse

31) La Varsovienne

a) Entrée

b) Adage

c) Variation I

d) Variation II (for Miss Riccardi)

e) Coda

32) Grand Pas de Deux (supplement for Giselle, 1888)

a) Adage

b) Variation du Comte

c) Variation de Mazourka (newly written for Miss Draeger)

d) Coda

33) Scène – Entrée de la Comtesse

34) Scène Dramatique

35) Pas Seul de la Comtesse (for Miss Nicholson)

36) Cracovienne Générale (1883)

37) Scène Finale

1900 Revival

In 1900 ballet was revived for the Sarah Nicholson, who had held the position of the most senior première danseuse since Draeger’s 1894 departure.

Rôles

Mazourka: Sarah Nicholson

Musical Revisions

Nicholson considered restoring the original Adam variation in the Pas de Grisi, as she believed that it better suited her talents than the variation that Draeger had interpolated in 1894. However, she was advised by Richard Hague (Thompson’s successor) to dance it, believing the challenge would be beneficial for her. Nicholson eventually relented and decided that she would dance Draeger’s variation.

The 1883 variation for the Ambassadress in La Varsovienne was restored, with Riccardi’s 1894 variation being discarded.

The Grand Pas de Deux Noble of the third act was again presented in a new version. Adam’s original Adage and Coda were restored, the Allegretto was not, but as in 1883, the variations for the Comte and Mazourka were not by Adam, but were interpolations. The Comte danced the variation from Draeger’s 1888 Giselle pas that had been interpolated in 1894 while Nicholson’s Mazourka danced the new variation that had been composed for Draeger in 1894. Though the choreography of the variations remained much the same from the 1894 revival, the choreography of the Adage and Coda were revised to be more technically demanding than the 1883 revival.

Résumé des Scènes et Danses

Acte 1

1) Introduction

2) Scène Première – Les Veneurs et Gardes de Chasse

3) Scène – Entrée d’Yvan et Yelva

4) Scène – Entrée du Comte

5) Scène – Le Partie de Chasse

6) Scène – Entrée d’Yelva

7) Scène – Entrée de la Comtesse

8) Scène – Entrée de Mazourka

9) Scène – Les Paysans

10) Scène – Les Nobles

Divertissement

11) Pas de Deux (arranged in 1894)

a) Entrée

b) Adage

c) Variation d’Yvan

d) Variation d’Yelva

e) Coda

12) Pas de Grisi

a) Andante

b) Allegro non troppo

c) Variation de Mazourka (supplemental variation for Fleur de Lys in the Grand Pas des Corbeilles in the 1878 revival of Esmeralda) (1894)

d) Coda

13) Mazourka

14) Scène – La Colère de la Comtesse

15) Scène – Mazourka et l’Aveugle

16) Scène Finale – La Transformation

Acte 2

Scène 1

17) Entr’acte et Scène Première – La Cabane du Vannier

18) Scène – Entrée d’Yvan et Yelva

19) Scène de La Dispute

20) Pas Villageois (arranged in 1894)

a) Menuet

b) Polka à Coup de Bâton

c) Coda – Louré

21) La Toilette de Mazourki

Scène 2

22) Entr’acte et Scène – Mazourka et Le Magicien

23) Scène – Le Toilette de Mazourka

24) Scène – Entrée du Comte

25) Scène – La Leçon de Danse

26) Pas de Leçon (1894)

a) Adage

b) Allegretto

c) Variation du Maître à Danser

d) Variation de Mazourka

e) Coda

27) Scène Finale

Acte 3

28) Entr’acte et Scène du Bal (expanded 1883)

29) Scène – Les Invités

Divertissement

30) Pas de Fantaisie

a) Andante

b) Allegretto

c) Variation à Deux

d) Coda-Valse

31) La Varsovienne

a) Entrée

b) Adage

c) Variation I

d) Variation II (1883)

e) Coda

32) Grand Pas de Deux Noble

a) Adage (original Adam, written in 1845)

b) Variation du Comte (supplemental variation for Albrecht from a Pas de Deux written for Miss Draeger in the 1888 revival of Giselle)

c) Variation de Mazourka (supplemental variation for Miss Draeger Mazourka in the Grand Pas de Deux in the 1894 revival of The Devil to Pay)

d) Coda (original Adam, written in 1845)

33) Scène – Entrée de la Comtesse

34) Scène Dramatique

35) Pas Seul de la Comtesse (1894)

36) Cracovienne Générale (1883)

37) Scène Finale