La Sylphide

Or The Sylph

Ballet pantomime in two acts on 12th March 1832 at the Théâtre de l’Académie Royale de Musique, Paris

Choreography: Filippo Taglioni

Music: Jean Madeleine Schneitzhoeffer

Premiers Rôles

La Sylphide: Marie Taglioni

James: Joseph Mazilier

Effie: Lise Noblet

Plot

Summary

Acte 1

In the hall of a Scottish farmhouse, James Ruben, a young Scotsman, sleeps in a chair by the fireside. A sylph gazes lovingly upon him and dances about his chair. She kisses him and then vanishes when he suddenly wakes. James rouses his friend Gurn from sleep, and questions him about the sylph. Gurn denies having seen such a creature and reminds James that he is shortly to be married. James dismisses the incident and promises to forget it.

James’ bride-to-be, Effie, arrives with her mother and bridesmaids. James dutifully kisses her, but is startled by a shadow in the corner. Thinking his sylph has returned, he rushes over, only to find the witch, Old Madge, kneeling at the hearth to warm herself. James is furious with disappointment.

Effie and her friends beg Old Madge to tell their fortunes, and the witch complies. She gleefully informs Effie that James loves someone else and she will be united with Gurn. James is furious. He forces Madge from the hearth and throws her out of the house. Effie is delighted that James would tangle with a witch for her sake.

Effie and her bridesmaids hurry upstairs to prepare for the wedding, and James is left alone in the room. As he stares out the window, the sylph materializes before him and confesses her love. She weeps at his apparent indifference. James resists at first, but, captivated by her ethereal beauty, capitulates and kisses her tenderly. Gurn, who spies the moment from the shadows, scampers off to tell Effie what has happened.

When the distressed Effie and her friends enter after hearing Gurn’s report, the sylph disappears. The guests assume Gurn is simply jealous and laugh at him. Everyone dances. The sylph enters during the midst of the revelry and attempts to distract James.

As the bridal procession forms, James stands apart and gazes upon the ring he is to place on Effie’s finger. The Sylph snatches the ring, places it on her own finger, and, smiling enticingly, rushes into the forest. James hurries after her in ardent pursuit. The guests are bewildered with James’ sudden departure. Effie is heartbroken. She falls into her mother’s arms sobbing inconsolably.

Acte 2

In a fog-shrouded part of the forest, Madge and her companion witches dance grotesquely about a cauldron. The revellers add all sorts of filthy ingredients to the brew. When the contents glow, Madge reaches into the cauldron and pulls a diaphanous, magic scarf from its depths. The cauldron then sinks, the witches scatter, the fog lifts, and a lovely glade is revealed.

James enters with the sylph, who shows him her charming woodland realm. She brings him berries and water for refreshment but avoids his embrace. To cheer him, she summons her ethereal sisters who shyly enter and perform their airy dances. The young Scotsman is delighted and joins the divertissement before all flee for another part of the forest.

Meanwhile, the wedding guests have been searching the woodland for James. They enter the glade. Gurn finds his hat, but Madge convinces him to say nothing. Effie enters, weary with wandering about the forest. Madge urges Gurn to propose. He does and Effie accepts his proposal.

When they all have left, James enters the glade. Madge meets him, and tosses him the magic scarf. She tells the young farmer the scarf will bind the sylph to him so she cannot fly away. She instructs him to wind the scarf about the sylph’s shoulders and arms for full effect. James is ecstatic. When the sylph returns and sees the scarf, she allows James to place it around her trembling form.

As James embraces the sylph passionately, her wings fall off, she shudders, and dies in James’ arms. Sorrowfully, her sisters enter and lift her lifeless form. Suddenly, a joyful wedding procession led by Effie and Gurn crosses the glade. James is stunned. James directs his gaze heavenward; he sees the sylph borne aloft by her sisters. James collapses. Madge exults over his lifeless body. She has triumphed.

History

Original Production

La Sylphide premièred on 12 March 1832 at the Salle Le Peletier with choreography by the groundbreaking Italian choreographer Filippo Taglioni and music by Jean Madeleine Schneitzhoeffer.

Taglioni designed the work as a showcase for his daughter Marie. La Sylphide was the first ballet where dancing en pointe had an aesthetic rationale and was not merely an acrobatic stunt, often involving ungraceful arm movements and exertions, as had been the approach of dancers in the late 1820s. Marie was known for shortening her skirts in the performance of La Sylphide (to show off her excellent pointe work), which was considered highly scandalous at the time. The use of pointework and the shortened skirt (which would later evolve into the tutu) would lay the foundations for the works of the later Romantic and Classical eras.

The ballet’s libretto was written by Adolphe Nourrit, the first Robert in Meyerbeer‘s Robert le Diable, an opera which featured Marie Taglioni in the rôle of Héléna in the famous Ballet of the Nuns. Nourrit’s scenario was loosely based on a story by Charles Nodier, Trilby, ou Le Lutin d’Argail, but swapped the genders of the protagonists: a goblin and a fisherman’s wife of Nodier; a sylph and a farmer in the ballet.

The scene of Old Madge’s witchcraft which opens Act II of the ballet was inspired by Niccolò Paganini’s Le Streghe, which in its turn was inspired by a scene of witches from Il Noce di Benevento (The Walnut Tree of Benevento), an 1812 ballet by choreographer Salvatore Viganò and composer Franz Xaver Süssmayr.

The version created by August Bournonville for the Danish Royal Ballet in 1836 is better known today than the original 1832 Taglioni-Schneitzhoeffer version. Bournonville had originally intended to present a revival of Taglioni’s original version in Copenhagen, but the Paris Opéra demanded too high a price for Schneitzhoeffer’s score. Thus, Bournonville decided to created his own version of La Sylphide, basing his production on the original libretto with a new score by Herman Severin Løvenskiold. His version premièred on 28 November 1836, with Lucile Grahn as the Sylph and Bournonville himself as James.

Selected Revivals

1835

Location: Imperial Bolshoi Kammeny Theatre, St Petersburg

Staged by Antoine Titus for Luisa Croisette.

28 September [O.S. 6 September] 1837

Location: Imperial Bolshoi Kammeny Theatre, St Petersburg

Staged by Filippo Taglioni for Marie Taglioni.

5 March 1852

Location: Théâtre de l’Académie Nationale de Musique, Paris

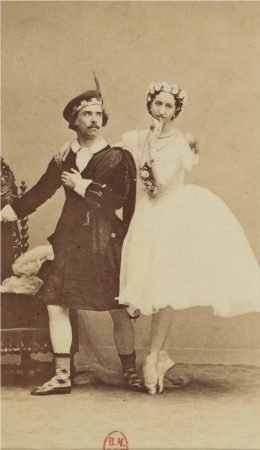

Staged for Olympia Priora with Arthur Saint-Léon as James.

20 October 1858

Location: Théâtre Impérial de l’Opéra, Paris

Staged for Emma Livry with Louis Mérante as James. Louis Clappison composed a new Pas de Deux (called the Pas Nouveau in the archives) for the second act, replacing the original 1832 Pas de Deux of Taglioni.

January 1892

Location: Imperial Mariinsky Theatre, St Petersburg

Staged by Marius Petipa for Varvara Nikitina with musical revisions by Riccardo Drigo. Pavel Gerdt portrayed the rôle of James and Maria Anderson portrayed the rôle of Effie. Among Drigo’s additions were a Danse Écossaise, a Pas des Sylphides, an Adage for James and Sylph and a Variation for Nikitina as the Sylph. The Variation composed by Drigo is better known today as the Paquita Étoile Variation, often heard in the Paquita Grand Pas Classique.

London Revivals

1895 Revival

When William Thompson set about reviving the ballet for Sarah Nicholson in 1895, he had high hopes for the ballet. It was a definitive work (arguably the defining work) in the history of ballet, being the first full length ballet danced en pointe where pointework was used to serve the story and its aesthetic world, not merely as an acrobatic feat as had been the approach of dancers of the late 1820s. The success of La Sylphide propelled Marie Taglioni to stardom and eventually into legend, still being hailed today as one of the greatest, if not the greatest ballerina who had ever lived. It was a key work in the development of Romantic Ballet which would reach its zenith in Paris (and London) in the 1840 with works such as Giselle (1841), The Peri (1843), Ondine (1843) and Esmeralda (1844) and would pave the way for the Russian successes of the 1860s and beyond.

Thompson wished to revive the work for its place in the history of the art-form, and Nicholson was receptive to portraying a rôle so associated with famous danseuses; namely Marie Taglioni, Emma Livry (both in Paris) and most recently Varvara Nikitina who performed the role in St Petersburg in 1892. Management, however, was skeptical that such an ‘old’ ballet would please the London public, who by now were accustomed to grander works (such as Thompson’s Pygmalion of 1893 and his revival of Esmeralda of 1894). Despite the concerns, Thompson was eventually allowed to proceed with the revival, necessitating an “unusually high” price to be paid to secure the score from Paris (more expensive than the other “unusually high” price had been paid to secure Hertel’s score for The Wayward Daughter from Berlin in 1886).

Once the score was received, Thompson set to work revising the ballet in “modern style”, rearranging much of the choreography and revising and supplementing Schneitzhoeffer’s original score with new musical additions. Due to its lustre and legend, the première and first few performances were well attended. However, despite Thompson’s efforts the ballet struggled to find its footing on the London stage and attendance began to fall. The critics largely dismissed the work as a trifle; concluding it could neither compare to more dramatic Romantic ballets such as Ondine and Giselle nor to the spectacle of ballets such as Pygmalion or The Corsair nor to the wit and charm of ballets such as The Wayward Daughter or The Devil to Pay.

One critic dismissed the production saying:

“Though the scenario is pleasing enough, and Miss Nicholson dances the airy Sylph with no small grace, the entire work strikes one rather as a faded water-colour than as the vibrant oils of Mr Thompson’s other productions.”

Another, who was more appreciative of the effort, still stated:

“Mr Thompson has afforded us, in this revival, something of the gaslight of our grandmothers’ day, as we return once more to that Scottish farmhouse wherein ballet may be said to have been born. Miss Nicholson dances with an admirable poetry, and Mr Hale’s portrayal of the Scotsman displays with great truth his rightful fascination with the sylph. Mr Thompson has arranged several new dances — two in the first act, a Pas de Trois and a Pas de Sept, and in the second, a Pas des Sylphides — which, as ever, exhibit those pleasing groupings and varied figurations for which our ballet-master is so justly esteemed.

Yet one cannot but reflect, when presented with so old a thing made new, whether Mr Thompson’s efforts might not have found a worthier field elsewhere. The very soul and spirit of La Sylphide seem aware that they belong to ages past, and thus the work presents itself with a grandeur to which it is almost ill-suited. One is compelled to wonder whether it were not better to leave legend as legend, rather than to cheapen it by drawing it down from its airy grave into the full light of our modern reality.”

Thompson was reportedly very disappointed with the reception of the ballet, both by the critics and the audience. The revival seemed to have been a personal ambition of his, and to have management proved right as to its reception called into question his own judgement as balletmaster. Thankfully, the revival of Coppelia the same season (also with Nicholson as Swanhilda) fared much better, though it was clear to all backstage that his heart truly lay with The Sylph, not with Coppelia. Thompson is alleged to have lamented:

“It seems the audience are displeased with La Sylphide…and it would also seem the audience have lost their taste for art.”

Rôles

The Sylph: Sarah Nicholson

James: James Hale

Effie: Harriet Linwood

Gurn: Charles Jennings

Pas de Trois ladies: Anna Blunt and Marie Saunier

Sylphs: Clara Whitmore, Lucia Rinaldi and Giulia Moretti

Musical Revisions

As part of Thompson’s efforts to revise the ballet in ‘modern style’ (and so please the public), musical revisions were undertaken by Auguste Péchard.

A Pas de Trois was added to the first act for Gurn and two female sujets, replacing the original Pas de Deux that had been danced by two unnamed sujets. The music for this pas was not by Péchard but was by Bardet, and was written as an insertion into Act 1, Scene 5 of the 1882 production of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet at the Lyceum Theatre. At its première it was danced by the leading dancers of Thompson’s troupe (at that time still stationed at Her Majesty’s Theatre): Isabella Velluti, Marguerite Lemoine and Samuel Penrose.

A Pas d’Action (also called Pas de Sept) was added for James, Effie, the Sylph and four female coryphées, replacing the original Pas de Trois for James, Effie and the Sylph. Nicholson’s Sylph flitted in and out of pas, confusing all present due to being only visible to James.

Variation for Mr Hale as James in the Pas d’Action, composed by Auguste Péchard (1895)

Thompson disliked Schneitzhoeffer’s original pas for the second act and had wished to use the replacement pas that Louis Clappison had composed for Emma Livry’s 1858 debut. However, the Opéra refused to send the music, stating that the pas belonged to Mlle Livry and following her death to her mother, Mme Célestine Emarot, and following Mme Emarot’s 1892 death to her next of kin. The Opéra stated that if Thompson wished, he could write to Mme Emarot’s next of kin for their permission to use the pas, but they would not do so on his behalf. Predictably, this response irritated Thompson, who believed that the Opéra was deliberately annoying him with its refusal to send the pas.

Thus, he resolved to create his own pas, turning to Péchard to provide the music. This resulted in the new Grand Pas des Sylphides being composed to replace Schneitzhoeffer’s original pas. The pas included variations for each of the three solo sylphs and a variation for Nicholson’s Sylph. Nicholson’s harp variation (composed for Covent Garden’s Prussian harpist Friedrich Mandl) was later interpolated into the 1901 revival of Ondine as the Ondine’s variation in the Grand Pas des Nayades and was retained as the traditional variation for the pas in subsequent revivals.

Résumé des Scènes et Danses

Acte 1

TBC

Acte 2

TBC